Aged under mountain mist, pressed with reverence — this is tea as living heritage.

In the highlands of southern Yunnan, where dawn breaks through layers of silvery fog, there lies a quiet rhythm known only to the ancients. Brown Mountain—Manpo in local dialect—rises like a sleeping dragon cloaked in emerald canopies. Here, among moss-covered roots and centuries-old trunks, grows a tea that doesn’t merely steep—it remembers. The Brown Ancient Rhyme Pu’er Tea begins not in fields, but in forests; not with machines, but with morning dew trembling at the edge of a leaf.

The air hums with stillness as tea farmers move between towering Camellia sinensis var. assamica trees, their bark etched by time. These are no ordinary plants—they are elders, some over 300 years old, drawing minerals deep from untouched soil. At first light, hands gently pluck two leaves and a bud, guided less by clock than by instinct. You can almost hear the soft plink of dew falling onto moss below—a sound older than words, carried forward in every compressed brick.

The alchemy of ripening: microorganisms transform raw leaves into deep, mellow complexity.

From forest to factory, transformation unfolds slowly, respectfully. Unlike green teas rushed to halt oxidation, ripe pu’er embraces change. Our master fermenters use the traditional wo dui (wet-piling) method—a dance of moisture, microbial life, and precise temperature control over weeks. It’s an art passed down through generations, where intuition matters more than instruments. Too hot, and the tea burns; too cold, it stalls. But when balanced just right, something magical happens: bitterness mellows, earthiness deepens, and a rich, rounded character emerges—like autumn turning to winter in a single breath.

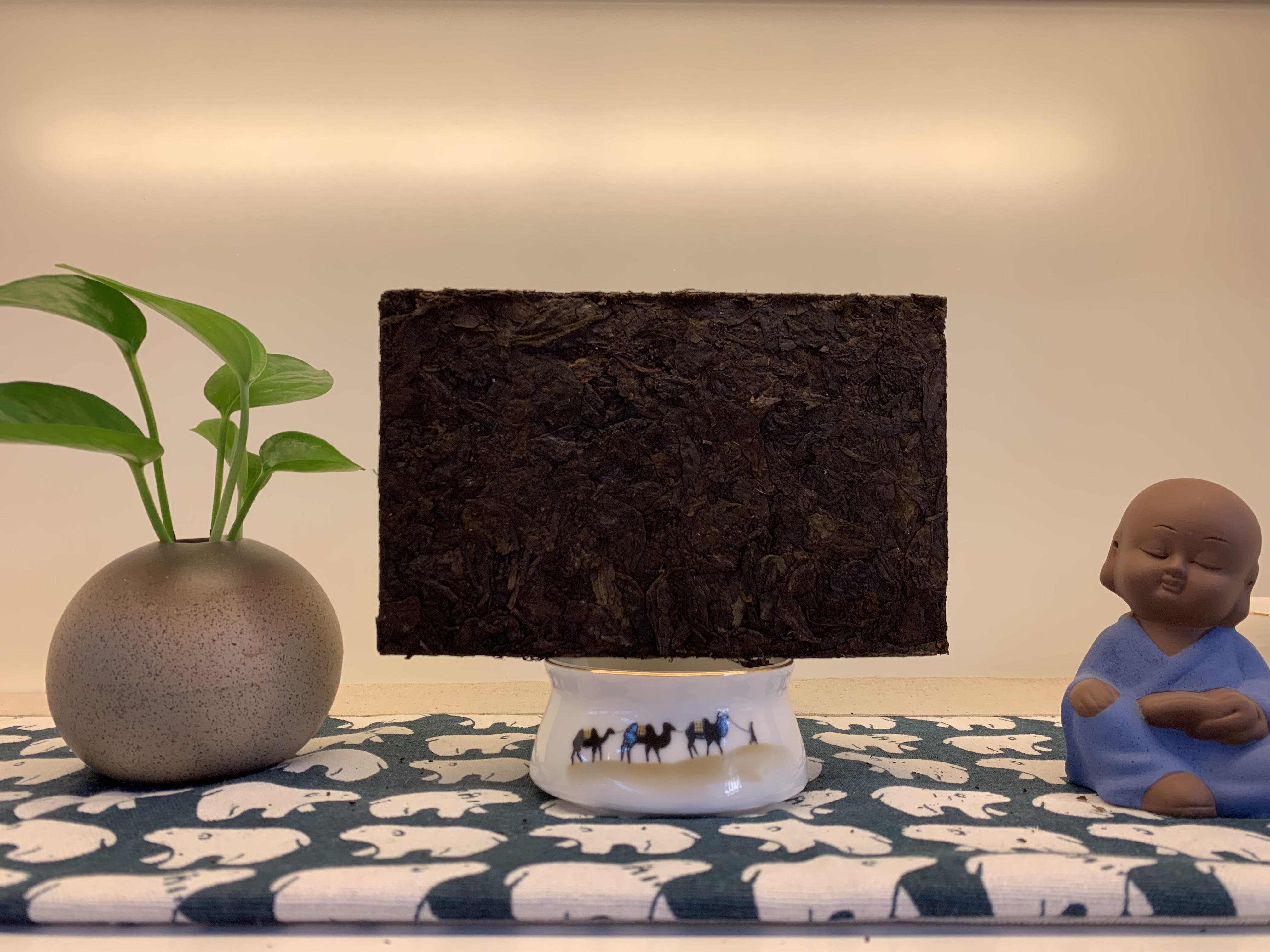

Then comes compression. Each batch is carefully weighed and steamed before being pressed into dense bricks using wooden molds and manual force. This isn’t mass production—it’s sculpture. The pressure must be firm enough to preserve integrity during aging, yet gentle enough to allow future breathing. The resulting brick feels substantial in hand, its surface slightly uneven—a mark of authenticity, not flaw.

What happens next defies haste. Stored in climate-controlled aging cellars reminiscent of wine caves, these bricks rest in darkness, nurtured by ambient microbes. Over months and years, their essence evolves: sharp woody notes soften into aged cedar, then drift toward camphor and dried longan, finally settling into a rare honey-zhang aroma—sweet, resinous, profoundly calming. One imagined entry from a tea master’s journal reads: *Year One: damp forest floor. Year Two: dried dates and sandalwood. Year Three: silence has a scent, and it smells like this.*

A pour reveals luminous amber—thick, clear, alive with layered fragrance.

To taste is to travel. Warm the gaiwan, awaken the leaves with a quick rinse, then inhale: beneath the aged musk lingers a whisper of osmanthus and dried apricot. The liquor pours like liquid topaz—clear, radiant. On the palate, it glides like silk over the tongue, full-bodied without weight. There’s depth here, a resonant warmth that settles in the chest, followed by a lingering sweetness that climbs back up the throat. Compare this to common ripe pu’ers made from younger bushes, often flat or overly earthy, and the difference is unmistakable: this is terroir expressed through patience.

How you brew shapes the story. Use a Yixing clay pot for slow infusions—each steep revealing new dimensions, like chapters unfolding. Or opt for a gaiwan with short steeps to capture its brighter top notes. Either way, each session becomes ritual: water heating, steam rising, mind slowing.

In a world obsessed with speed, this tea offers rebellion in the form of calm. Modern science confirms what tradition has long known—pu’er aids digestion, supports metabolism, and soothes post-meal discomfort. But beyond biochemistry, there’s psychology: the act of brewing grounds us. For creatives facing blank screens, or professionals navigating endless meetings, one bowl of this dark nectar restores presence. It’s not escape—it’s reconnection.

And for collectors? Each brick bears a unique batch code, traceable to its harvest origin and fermentation date. With wild arbor material becoming increasingly rare due to ecological protection efforts, genuine ancient tree pu’er is quietly gaining value. This isn’t speculation—it’s stewardship. When you hold this tea, you’re holding decades of growth, months of craft, years of aging. As one connoisseur put it: *Now we drink time. Later, we’ll drink history.*

In an age of instant everything, choosing a tea that demands waiting feels radical. Yet perhaps what we truly crave isn’t faster results—but deeper meaning. The Brown Ancient Rhyme doesn’t rush. It waits. It transforms. It endures. And when you finally pour a cup, you’re not just drinking tea. You’re listening to the low voice of mountains, whispering across centuries.

So ask yourself: Are you ready to press pause—for ten minutes, for ten years—and savor what only time can create?